Entry: Capital

Capital: Automatic Subject – Animate Object

Marx’s project aims to understand the determination and concretisation of class society. As a society that contains racial and gendered determinations, which constitute oppressions lasting across generations, grasping what upholds this social formation implicates all facets of our social and individual lives. Ultimately, Marx wants to understand how a society can be liberated from oppressions that are determined by the capitalist system. To do this, Marx examines how class formations not only emerge, but what it is that so deeply sustains them. One factor Marx emphasises as sustaining class formation is the capitalist deprivation of human subjectivity itself. In other words, the deprivation of human agency[1] to shape our own lives through determining our own social conditions. In capitalism, agency is suppressed not only by “false consciousness”, which sees the appearance of capitalist exchange as truly based on individual agency and equal exchange, but by practical activity that renders subjects objects and objects subjects.

Marx reveals that capital’s exchange abstraction not only reduces humans to objects of economic production and calculation, deprived of “humanity”[2], but makes humans incapable of constructing a social relation whereby they transcend their economic function as objects of production and calculation. If the determining force shaping society cannot be located within the human individual, trans-individual or “collective” subject, Marx concludes that the primary agent shaping social conditions must be located elsewhere. This non-human element independently driving the historical process is not, for Marx, nature, which Marx locates in a metabolic relation with humanity and, therefore, not something opposed to human experience. Autonomy is, instead, located objectively at the core of what constitutes our social formation itself: capital.

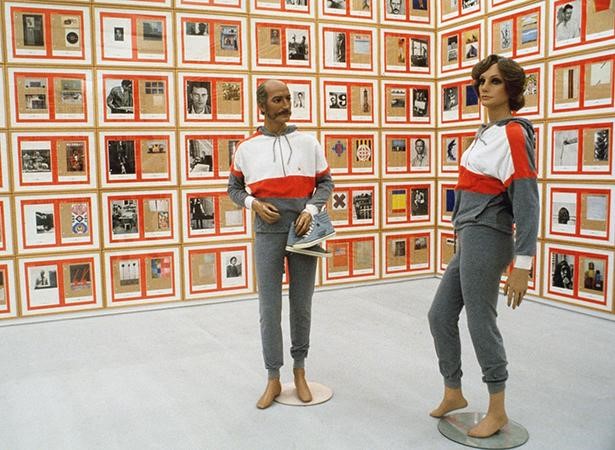

Hanne Darboven, “Kulturgeschichte 1880–1983 (Cultural History 1880–1983)”[3]

This independent actor, capital, is a human creation that, while superseding and determining collective formation, cannot come into being without human action. Action transmits intention, ideas and sensuousness to the objective form in which the actor, or actors create. As such, action animates objects of production with knowledge and thought. Marx understands this dynamic to lie at the core of humanity – a capacity to construct social conditions and produce sensuous, objective culture (such as art and literature).

Capital is endowed with quasi-subjectivity – with the capacity to act independently of human agency – for two reasons, both equally necessary and interrelated. First, because the living actions of human beings, made of organic matter – of brains, muscles and nerves – are objectified in capital’s constitution, where objectively embedded actions constitute ‘abstract labour’. For Marx, abstract labour is the substance of value for capital; labour measured by time and accounted for by money is, as abstract labour, a subjectively-conjured abstract representation making up capital’s essential property. In this way capital is an object made up of human subjective properties. The second reason is that the exchange relation forming the passage of human action to abstract representation is based on the exchange of labour. Only in a configuration where labour is exchanged do capitalist exchange relations arise. Where the exchange of labour unfolds, those who exchange their labour do so because they do not own their own means of production. Otherwise, they would simply exchange things and not labour (capital’s grounding in private property requires that many of us do not own property apart from our own labour power). When the exchange of labour (human practice itself) becomes the predominant exchange relation, the movement of commodity exchange[4] becomes the primary dynamic constituting the conditions of production of social relations. Marx uses the term fetishism to describe this process not only because the object produced is endowed with the character of human sensuousness through the creation of abstract values on account of abstract labour (labour measured in time and therefore endowed with an abstract quantity), but because the abstract value created – the exchange value as distinct from its use value – seemingly expands and grows independently of its conditions of production. The appearance of self-expansion makes the accumulation of capital life-like: it is an object endowed with the appearance of subjective capacity.

Marx’s explanation of commodity fetishism, however scientific, borders on the mystical when he insists that it entails the animation of the otherwise inanimate, illustrated by his famous example of the table whose objective status is reversed, or turned “upside down”, to render the table a “dancing” subject. Marx explains,

The form of wood for instance, is altered if a table is made out of it. Nevertheless the table continues to be wood, an ordinary, sensuous thing. But as soon as it emerges as a commodity, it changes into a thing which transcends sensuousness. It not only stands with its feet on the ground, but, in relation to all other commodities, it stands on its head, and evolves out of its wooden brain grotesque ideas, far more wonderful than if it were to begin dancing of its own free will.[5]

The act of creation, or the making of an object through human effort, endows the object of creation with the product of that very effort. Human action, effort and thought become objectified in a thing, as in the case of human intellectual knowledge objectified in technology, infrastructure and art – from productive forms to genre forms. According to Marx, fetishism is the specific form of abstraction of human action internal to capital. The production of such fetishism arises not through abstraction qua abstraction.[6] Instead, in the context of wage labour, the product of labour does not become merely an externalised expression of human agency, which might contribute to the reproduction and upkeep of our lives or objective shared culture (constituting community). Rather, the externalisation of human effort is instrumentalised for the purpose of generating ever more value.

Capital is the unity of the accumulation of this growth, meaning that capital is an object in so far as it is an abstract representation of a metaphysical substance: the very human excess of effort extracted from the process of production. When the act of production (labour) is measured by units of time and allotted a wage measured monetarily, the act is homogenised and represented in the abstract as a unit that is exchangeable. Hence labour becomes a commodity that has a use value (the act of making) and an exchange value (wage). When represented as an exchange value, a worker’s actions become homogenous and internally undifferentiated. They are therefore representable in abstract units, exchangeable with anything else. In this process a portion of the time the worker endures is not represented by the wage, yet objectively stored in the commodity produced. Upon sale by the capitalist this unpaid portion appears again as profit kept by the capitalist who owns the means of production, or the context in which labour takes place. This produces what Marx calls surplus value. In the case of surplus value, the content or substance of value (labour) is not exchanged for a wage but accumulated by the capitalist upon sale of the commodity,[7] allowing for capital to accumulate more capital. The wage exchange (the capital-labour relation) is based on the exploitation of labour and therefore it is labour that supplies the excess of human effort that lies behind value’s growth.

This explanation supplies the foundation for why Marx uses the enigmatic term “automatic subject”[8] to describe capital. If human action is endowed with the ontological property of agency, or subjectivity, then when socialised as homogenous labour through its measure in time and represented as a value (labour equal to all other labour because measured and objectified as value, despite any practical difference), this agency and subjectivity makes up the substance of what is accumulated as capital. Capital, endowed with human effort, retains the capability to supersede the individual’s capacity to act out the very subjective freedom that supports the dynamic. Within capitalism, the purpose of collective action is directed towards the accumulation of value, and, consequently, to the accumulation of more value represented as capital. Capital becomes animated as the subject of the process and humanity becomes subject to the process of the accumulation of capital. In so doing, humanity is determined as an abstraction purposed for the interest of accumulation of value. Humanity, therefore, becomes deprived of the very thing that allowed for the process to occur: the subjective agency to act.

Consequently, capitalism reduces human life to an objective medium for the reproduction of capital. Thus, capital – not humanity – constitutes the agentive subject of the accumulation process. Human life engages with capital’s social relation not as a subject endowed with agency but as a necessarily “other” ontological foundation. While completely dependent on the human labour that produces the substance of value as abstract labour, capital takes on its fetish character to seemingly reproduce without labour. Capital appears to be a self-moving “automatic subject” of the process of accumulation. Capital becomes animate.

Philosophically speaking, capital is an animate object or an objective subject of a process. While the modern human subject represents the unity of a process of personification (the I of a relational self-conscious being that thinks), capital is interpreted as subject because it represents the unity of historical acts that determine social relations as a mode of production. Capital’s process is characterised by the manner in which objects circulate: commodities such as labour, money, technological hardware/software and consumer goods move in such a way as to reproduce capital. Circulation is determined by the movement of the subject reproducing itself, which is itself an object: Capital. Capital is therefore a subject-object: an animate (in its life-like, self-reproducing appearance) object; and an automatic (in its objective foundation in human production) subject: two oppositional characterisations of the same antinomy.

It is the primacy of the abstraction of capital that makes this subject-object possible. Only when a category of thought (a logic/abstraction) is given primacy over being do subject-objects philosophically come into being. Yet, in his materialism, Marx remained sceptical of philosophies that accorded primacy to abstractions in the guise of metaphysical truths (as in Hegel’s Spirit); Marx regarded these as misconceived overdeterminations of material, practice and, ultimately, life by conceptual and formal thought. However, Marx did think that capital was a historical object, or social form, that created a dynamic in which abstractions overdetermined practical life. Therefore, capital is a subject-object historically created by social practice. Here, the dichotomy between subject and object is dialectically understood: subjective and objective elements are generative of their very distinction. In the process of generating its distinction as an objective abstraction, capital becomes subject.

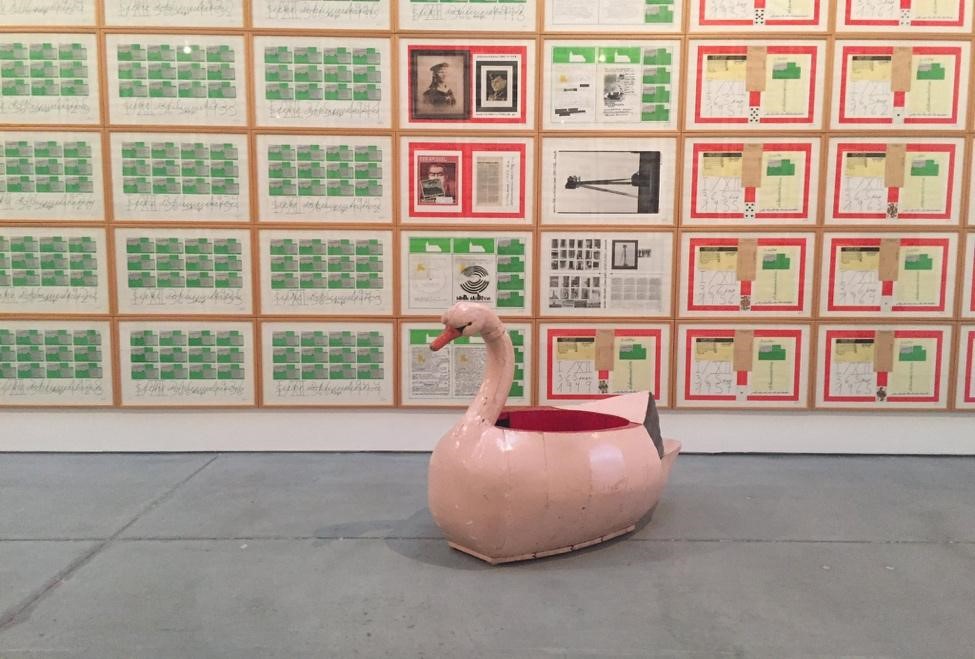

Hanne Darboven, “Kulturgeschichte 1880–1983 (Cultural History 1880–1983)”[9]

The world of abstract appearances, in which capital guides the circulation of commodities, exists as a “phantasmagoria”. Here, the animation of the objective world conceals the real relations of production subjected to the movement of capital as an “automatic subject”. The ocular description employed emphasises capital’s apparent agency to determine social relations. Agency is of course the key element that renders the thinking of capital as subject possible. Yet, at the same time, capital’s agency is always for Marx an appearance that hides the real social relation. As such, capital becomes an animation of social relations. Like animation, where a still image appears in motion, the appearance of social existence within capitalist relations contradicts the real conditions of production.

The phantasmagoric system of relations within which capital exists are independent and alien from any subjective meaning (an abstraction from experience). Nonetheless, they represent the qualitative dimension of any individual’s social experience. In bourgeois society, individuals’ qualities become objective and unpaired from their personality, becoming objects within a world that can only be owned or exchanged, whilst the state of owning or exchanging are positions of subjection determined by the movement of capital as automatic subject itself. This leads to the fragmentation of experience where individuals treat their own ideas, abilities and even psychic states as quantifiable objects of the external world in which they can own and exchange.

Within the intellectual tradition in which Marx worked[10], that which rendered a subject a subject, or an individual an agent, was the self-conscious life of the individual. An individual (subject) thinks itself, predicates its own thoughts, and as such possesses a psychology. Yet in the world of appearances, in which subjects regard other subjects, the psychology of the other (as the place ‘will’ and therefore the possibility of autonomous thinking/action are located) is always assumed. This assumption of psychology brings more plausibility to the antinomy of the automatic subject of capital. At the level of appearance, capital is a subject, while its nature as automatic is understood through the critique of its fetish, which reveals the illusion of semblant autonomy or free movement. Capital appears as subject (self-reproducing its own conditions), but from the point of view of the social relations that produce the appearance (obscured by the appearance), capital is the automation of a social form purposed towards the growth of wealth (and not merely the distribution of resources for survival and care).

Agency alights from the perspective of self-consciousness’ externalisation where the individual subject becomes a relational subject developed and formed by the objective world (which exists within history). Self-consciousness necessarily entails looking out in order to look in, amounting to a reflection from the outside that determines inner life. Hegelian philosophy best articulates this process. For Hegel, the examination of the relationships between subject and object as a process of self-conscious becoming begat the theorisation of a universal subject of history (absolute Spirit); individual self-consciousness is overdetermined by this “Spirit” in such a way as to make each individual subject a product of the whole. In this way, the individual subject is not only wholly relational to all other subjects, but also a product of historical circumstance. The claim that capital is subject, far from an exorbitant anthropomorphism, is an interpretation of Hegel’s objective Spirit, understood by Hegel as the subject-object of history. However, in straying from the theological implications of “Spirit”, which is a religious universal concept that Hegel takes to be an ontological given, Marx interprets absolute Spirit as an objective manifestation of human production (manifest not only in thought but in practice, ritual and infrastructure). Marx, with an explicitly modern eye, locates the subject of history in capital: the automatic subject that will necessarily constitute a subject-object. Using Hegelian thought, Marx undermines the universal ontological truths of theology. But Marx departs from Hegel to understand the dominance of economic social form as the determining the movement of history, transposing metaphysics from given truths (however processual) to the result of collective practice.

The appearance of an automatic subject, like an animate object, is what we necessarily see even if we know the appearance does not represent its own conditions of production. Animation, a practical method that renders images ostensibly mobile, results from the combination of social form (as in forms of illustration and media) and the essential characteristics of life, illustrating the core of the subject-object antinomy as an antinomy of life and form. Human life upholds capital’s social form. Through social practice, human life provides the substance of value that gives capital its “life-like” character; and, through subjection to form, it bares the different forms of appearance of capital (such as wage, rent, and the general mediation of money for survival).

The contradiction between life and form in Capital is much like Lukacs’ version of the Kierkegaardian gesture, as he understands it in his essay The Foundering of Form against Life: “there is no explanation, for what is there is more than an explanation, it is a gesture”. While for Lukacs the gesture, which is the movement of life, “always reacts back upon the soul that makes it”, what Marx reveals is that in capitalist social relations, gesture (practice) retrospectively constitutes the individual in subjection to capital’s movement. To understand and appreciate what sustains capitalist social form and its corresponding systems of oppression so deeply, Marx’s contends that analyses cannot merely understand the technical distribution of wealth and its intersection with identity (as offered by most economic critiques coming from the left); rather, we must explain the subjection of life to social form: a complex dynamic taking place between and through subjects and objects. Far from a mere articulation of objective process, the theorisation of capitalist form as ‘automatic subject’ permits a closer understanding of lived experience. As Lukacs wrote, ‘“form” is neither subjectively conjured nor objectively imposed; it holds out the possibility for a mediation and even indissolubility of the subjective and objective realms.”’[11] Form animates the subject and in so doing re-shapes life, creating it anew.

Rebecca Carson

[1] An agent is not merely a free individual or the author of an action, but a subject situated within relations that co-determine an action, implying the giving way of the dualism between passive and active when thinking about the possibility and limits of free will.

[2] A ‘species-being’ that, although it exists not in conditions of their own choosing, is marked by being collectively endowed with the capacity to shape social conditions.

[3] Hanne Darboven, Kulturgeschichte 1880–1983 (Cultural History 1880–1983), 1980–83. Installation view, DIA:Chelsea, Dia Art Foundation, New York. Photo: Cathy Carver, 1996. © Hanne Darboven Stiftung, Hamburg / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2015.

[4] The predominance of the abstraction of exchange value, appearing as price, over use value or the usefulness of the good sold.

[5] Karl Marx, Capital Volume 1, trans Ben Fowkes (London: Penguin, 1990), 163–64.

[6] As we might find human effort objectified in such a way as to encourage our own development as sensuous beings, as in the case of the objectification of human effort in an artwork.

[7] The commodity is not sold for more than it is worth, rather, the labour producing the commodity is not paid for in the full amount that is gained through the sale, allowing the capitalist to keep a portion of the value that the commodity is sold for. In this way capital appears to grow when in fact the accumulation of more value is based on the exploitation of labour.

[8] Marx uses this term on p. 255 in Capital Volume 1, in the section ‘The General Formula for Capital’, in order to describe the life of self-valorising value, or capital as having a life function.

[9] Hanne Darboven “Kulturgeschichte 1880–1983 (Cultural History 1880–1983)”, 1980–83, Installation view, M23projects, December 16, 2016, Dia Art Foundation, New York. © Hanne Darboven Stiftung, Hamburg / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2016. URL http://instagram.com/m23projects https://pic.twitter.com/hSDWpe1dnC

[10] German idealism.

[11] György Lukács, Soul and Form, trans. Anna Bostock (New York: Columbia University Press, 2010), 3.

Rebecca Carson is a lecturer in Critical and Historical Studies at the Royal College of Art, London in the Fine Arts Department, where she researches Marx and Philosophy. She is also a lecturer at Goldsmiths College where she teachinges Critical Studies in the Art Department. Her chapter “‘Money as Money: Suzanne de Brunhoff’s Marxist Monetary Theory’” appeared in Marx Inattuale, Edizioni Efesto (2019) and her article ‘“Fictitious Capital and the Re-emergence of Personal Forms of Domination’” in Continental Thought & Theory (2017). She is co-editor of ‘‘Politics of the Many’‘ with Bloomsbury where she contributed the chapter ‘The Marxism of Post-marxism.’ Her current research looks at Marx’s philosophical use of the term “life” in relation to Hegelian philosophy, in order to understand differentiated forms of subjection within the expanded reproduction of capital.